- EAT as a 'Davos for Food'

- The Planetary Health Diet

- The Great Food Transformation

- Interventionism and hard policies

- Criticism of the human health rationale

- Broader criticism

EAT's origins

The EAT initiative, founded in Scandinavia in 2013 by Gunhild Stordalen and Johan Rockström, aims to revolutionize global diets by reducing reliance on animal source foods and partially filling the resulting food gap with 'alternative proteins' [see elsewhere]. At that time, Stordalen was married to the Norwegian billionaire Petter Stordalen, whereas Rockström was the executive director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre [Turow-Paul 2016]. The EAT initiative gained momentum with its inaugural Food Forum in Stockholm in 2014, where the Prince of Wales and Bill Clinton voiced support [SRC 2014]. The Forum's mission was to unite 'experts and decision makers who can come together to change the way we eat'. Financial backing from the Wellcome Trust and the Stordalen Foundation in 2016 propelled the initiative forward, leading to the establishment of the EAT-Lancet Commission [Rockström et al. 2016; SRC 2016]. Spearheaded by Harvard's Walter Willett, the Commission then proposed a semi-vegetarian Planetary Health Diet [Willett et al. 2019], which rapidly became influential, being backed by the World Economic Forum, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, and United Nations, among others.

The hand of Davos

To revolutionize global diets, EAT operates trough various public-private partnerships, drawing inspiration from the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos [Leroy et al. 2023]. Being a self-declared 'Davos for food', EAT aims to 'add value to business and industry' and 'set the political agenda' [Richert 2014; Turow-Paul 2016]. This connection to Davos is no coincidence. Gunhild Stordalen was appointed as WEF Young Global Leader in 2015 [Eidem 2015], and maintains close ties with WEF's Børge Brende [Sæther 2015], a former Norwegian Minister, ex-chairman of the UN Commission of Sustainable Development [PMNCH], and member of the Steering Committee of the Bilderberg group [Bilderberg Meetings, accessed 03/01/2022]. He joined the WEF in 2008 and became WEF's managing director in 2011 [PMNCH], after he failed to get the position of executive director at UN Environment Programme (UNEP). In 2017, Brende was appointed as WEF's President [WEF]. Unsurprisingly, Davos has shown strong support of EAT. During the 2018 WEF conference in Davos, the EAT Foundation co-organized an event with, among others, Rabobank, the International Food Policy Research Institute, and the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition [IFPRI 2018]. Following the launch of the EAT-Lancet report in 2019, the WEF stated on its website that 'we all need to go on the planetary health diet to save the world' [WEF 2019]. A few days later, the report was also discussed at the 2019 WEF meeting in Davos, after which it was presented at the UN Headquarters in New York.

WEF's interest in food systems

The World Economic Forum's support for EAT's Great Food Transformation extends beyond mere sympathy. Food system overhaul is a component of the Davos strategy, highlighted in its Great Reset agenda. This includes an interest in the 'Future of Food', closely aligned with WEF's core activity of 'Developing Sustainable Business Models' [WEF 2020]. Convergence with the EAT agenda is unmistakable, both in concept and in practice. José María Olsen Figueres, the former CEO of WEF, is intricately linked to EAT as an 'EAT alumnus' [EAT]. His sister, Christiana Figueres, who is also UNFCCC’s ex-Executive Secretary and has declared to be in favour of expelling meat eaters from restaurants [Vella 2018], has ties to entities within the broader EAT network, such as the World Resources Institute, Unilever, the vegan-tech company Impossible Foods [Business Wire 2021], and business fronts such as Nature4Climate and We Mean Business. Taken together, EAT appears to function as the dietary arm of WEF, aiming to effect dietary change within a 'Transition Decade' (2020-2030) [WEF 2019]. To do so, the EAT/WEF network refers to a 'portfolio of solutions', including mock meat, lab meat, mycoprotein, and insects [WEF 2018a,b, 2020a,b; see also elsewhere]. In 2018, the WEF published 'Innovation with a Purpose: The role of technology innovation in accelerating food systems transformation' in collaboration with McKinsey & Co [Nayyar & Sanghvi 2018; WEF 2018]. Among other high-tech 'Fourth Industrial Revolution' interventions, also involving nutrigenetics, block chain, and virtual reality, the report made a case for 'alternative proteins'. Impossible Foods was cited as an example. A year later, WEF released a white paper on 'Alternative Proteins', prepared by the Oxford Martin School [WEF 2019], as part of its 'Meat: the Future' series.

EAT as public-private partnership

Given EAT's roots in the WEF, it is anticipated that its strategy will mirror the principles of the Davos philosophy. In tandem with WEF's Great Reset agenda, EAT's aim is to catalyse a profound global overhaul of the food system, coined as the Great Food Transformation [Lucas & Horton 2019]. The process is facilitated through high-level public-private partnerships, with support from WEF and close collaboration with NGOs, transnational policy organisations, and multinational corporations. References to EAT's Planetary Health Diet are already being integrated in policy frameworks worldwide to justify a transition to 'plant-based' eating, as evidenced in the EU's Green Deal and Farm-to-Fork strategy [European Commission 2020]. EAT's dietary proposal, therefore, transcends mere theoretical discourse; it should be understood a top-down policy blueprint grounded in the stakeholder capitalism model advocated by Davos [Leroy & Cohen 2019; Leroy & Hite 2020; Leroy et al. 2020, 2023]. Below, some of EAT's major allies will be listed, including factions within the United Nations, major agri-food corporations, and the vegan-tech industry. It will also be discussed how all these players emerged as a single constellation during the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit.

Alliance with the United Nations

To achieve its objectives, EAT frequently collaborates with factions within the United Nations, exemplified by the inclusion of WHO director Francesco Branca in its EAT-Lancet Commission. Additionally, EAT receives support from UNEP [UNEP 2019], which has gone so far as to label meat as 'the world's most urgent problem' while bestowing the highest environmental award of the UN upon vegan-tech companies Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods [UNEP 2018]. This close interaction with the UN is likely facilitated under the patronage of WEF. In bolstering its transnational influence, WEF has established an official partnership with the UN to accelerate the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [WEF 2019]. This 'strategic alliance' has faced criticism for what some view as a 'disturbing corporate capture of the UN' [FIAN 2020], resulting in a 'public-private UN' where the decisions of governments could be made 'secondary to multistakeholder led initiatives in which corporations would play a defining role' [Gleckman 2019]. Urgent global challenges, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and the COVID-19 pandemic are leveraged to create a sense of urgency [WEF 2019], with EAT's emphasis on a broken food system seamlessly aligning with this strategy.

Alliance with agri-food corporations

Some major agri-food corporations have openly embraced the WEF/EAT vision of dietary reform, seeing the radical restriction of animal source foods and their replacement by 'alternative proteins' (aka, 'food from factories') as an opportunity to tap into new market segments and further consolidate their already significant control over the food system. In 2017, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) formalized a partnership with EAT, known as Food Reform for Sustainability and Health (FReSH) [EAT; WBCSD; Coleman 2017]. This collaboration was announced during the Third Stockholm Food Forum, which aimed to 'bring science, policy and business together' [SRC 2016]. WBCSD participation in the Forum was focused on sharing progress on FReSH and exploring further collaboration among 'stakeholders across science and academia, policy-makers, business and consumer groups' [WBCSD 2017]. The WBCSD serves as an industry lobbying platform, representing various global agri-food corporations. FReSH has been characterized as a 'business-led initiative designed to accelerate transformational change in global food systems', bringing together 30+ companies, including leading food multinationals such as Nestlé, Danone, Unilever, Kellogg Company, and PepsiCo. These affiliated multinationals been actively promoting a transition to 'plant-based' eating [e.g., Pointing 2017; Wood 2018; Hyslop 2019], sometimes with strong anti-meat overtones [Kowitt 2019]. Unilever, for instance, aims to achieve €1bn sales from vegan products by 2027 [Smithers 2020], collaborating with the World Wide Fund for Nature and academia [WWF 2019; Askew 2020]. Also during the 2017 Forum, another multi-million dollar effort linked to EAT was announced: the 'Food and Land Use' Coalition (FOLU). Described as an effort that 'brings together science, business solutions and country implementation plans', FOLU acknowledges 'the invaluable contribution of Unilever, Yara International and the Business and Sustainable Development Commission in nurturing [its] initial development' [FOLU, accessed 02/01/2022].

Alliance with the vegan-tech industry

Because of its generally unsympathetic attitude towards livestock agriculture, EAT also attracted support from investors in vegan-tech who have an interest in animal rights agendas. Examples of vegan investors include Farm Animal Investment Risk and Return (FAIRR) and KBW's founder, prince Khaled bin Alwaleed, the son of a Saudi top investor (prince Alwaleed bin Talal, chairman of Kingdom Holding). FAIRR is an investor company of which the membership and wider supporting network comprises institutional investors managing many trillions in combined assets [Wikipedia 2020; FAIRR 2020]. It was founded in 2015 by Jeremy Coller, a vegan who wishes to 'end factory farming' [Pointing 2018], with the goal to put pressure on food companies to serve more imitation animal source foods [Robinson 2017]. Coller has a seat on the advisory board of the Good Food Institute, the leading lobby group for vegan-tech industries [GFI 2021]. FAIRR often interacts with EAT, as during the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit and the linked 'Rethinking Protein: Accelerating law and policy in the global food system' conference to 'concentrate on legal mechanisms to transition the food system' [FAIRR 2021]. As a vegan, bin Alwaleed refers to dairy as the 'root of environmental evil' [Halligan 2018] and like Coller is a member of the advisory board of the GFI [GFI 2021]. He is also influential within the EAT network [EAT 2020]. Together with several 'vegan leaders' with ties to GFI as well as with EAT's founder Stordalen, bin Alwaleed attended the Nexus Global Summit at the UN Headquarters in 2018 to discuss 'Next Generation Solutions for a World in Transition' [Flink 2018].

The UN Food Systems Summit

The strategic alignment between the UN and EAT/WEF became particularly notable during the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit. EAT's Gunhild Stordalen was appointed as chair of the Summit's Action Track 2, focusing on 'sustainable diets'. Her stated aim was 'to take full advantage of the Summit' and 'to force the kind of far-reaching changes that the world now desperately needs' [EAT 2020]. The WHO functioned as the Track's 'anchoring agency' [UN 2020]. Francesco Branca, an EAT-Lancet Commissioner and WHO director, had already made it clear that, within the food system, 'everything has to be reset [...] we have to have much smaller amounts of meat on our tables. We need to reset, and we need to adjust. We need the policies, the investments, on the supply side and the consumer side. The WHO will be working on the consumer side' (emphasis added) [Grillo 2020]. Action Track 2 was characterized by an outspoken anti-livestock sentiment, involving a vegan advocate and leader of the youth climate organization Zero Hour International as Youth Vice-Chair [Yeager 2019; UN 2020], the CEO of 50by40, an umbrella organization incorporating vegetarian pressure groups, vegan-tech industries, and animal rights activists, as Civil Society Leader [UN 2020], a vegan activist of the Chinese Good Food Fund as one of the workstream leaders [FT 2020], the founder of Brighter Green, an organization with an animal rights agenda (Mia MacDonald), and an academic from Chatham House and Harvard's Animal Law Department, previously affiliated with the Seventh-Day Adventist University of Loma Linda (Helen Harwatt). Moreover, the Good Food Institute (GFI) had been invited to 'lead the innovation pillar' of Action Track 2 and provide 'influence on the innovation thinking across all five action tracks' [GFI 2021]. Criticism was not only related to the clear anti-livestock bias, but to the Summit setup in general. Farmers, rights groups, and 'special rapporteurs on the right to food' from the UN lambasted the Summit as an opaque takeover by transnational corporations (including producers of ultra-processed foods), philanthrocapitalists, and the WEF [Via Campesina 2020, 2021; Canfield et al. 2021; ETC 2021; Fakhri et al. 2021; Langrand 2021; Nisbett et al. 2021; PCFS 2021; Vidal 2021; Saladino 2021]. How leaders of the Action Tracks were recruited has raised specific concerns because of the lack of transparency, absence of key expertise, and doubts about the origins of the funding [Canfield et al. 2021].

Composition

EAT's 'Planetary Health Diet' (or EAT-Lancet diet) is a semi-vegetarian or 'flexitarian' diet [Willett et al. 2019]. It sets a target for red meat at 5 kg/p/y (within a window of 0-10 kg/p/y) and suggests a total meat intake of 16 kg/p/y (within a window of 0-31 kg/p/y, both red meat and poultry). The suggested caloric contribution by all animal source foods is a mere 14% [% derived from Willett et al. 2019]. It prescribes small daily rations of beef or pork (each at 7 g) and eggs (13 g), in addition to some poultry (29 g), fish (28 g, but limited at 40 kcal), and dairy (250 g, limited at 153 kcal). For comparison, the limit for sugar was set at 31 g (120 kcal). The authors also endorse a meat-less vegetarian or vitamin B12-supplemented vegan approach as valid options.

Design rationale

It is important to take into account that the dietary calculations were 'not set due to environmental considerations, but were solely in light of health recommendations' [Mitloehner 2019]. This his is in contrast to what is commonly assumed about the Planetary Health Diet, and how it is usually promoted. Even if there has also been an assessment of how the diet aligns with planetary boundaries, the actual composition is based on health theory, as designed by Walter Willett from Harvard University.

Planetary Health and the Great Food Transformation

The idea of a global shift to a Harvard/Willett-designed low-meat diet pre-dates EAT and was already suggested a decade earlier as a 'Healthy Diet' transformation that should be implemented between 2010-2030 [Stehfest et al. 2009]. The 'Planetary Health' concept goes back to New Nutrition Science project conceptualized around 2000 and ending up in the Giessen Declaration of 2005 (already involving EAT's Tim Lang) [Cannon & Leitzmann 2006]. The concept of a Great Food Transformation towards the Planetary Health Diet generally fits within a mindset of grand transition schemes. Its content and wording not only echo the agendas and vocabulary of the WEF's 'Great Reset' [WEF 2021] and 'Great Transformation' [WEF 2012], they are also reminiscent of earlier 'Great Transformation' and 'Great Transition' projects.

The German connection: WBGU and PIK

A first example is provided by the 'Great Transformation' proposed by the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU), founded in the run-up to Maurice Strong's UN Earth Summit of 1992, and involving meat-free days, less livestock, and promotion of insect consumption [WBGU 2011, 2013]. WBGU is influential within certain fractions of the EU, the Vatican, and the UN. Its former chair [Hans Schellnhuber] embraces the idea of global governance through a UN-led Global Council and Planetary Court [Schellnhuber 2013]. He is also founding director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), where he was replaced in 2018 by the former director [Johan Rockström] of the Stockholm Resilience Centre, who co-founded EAT [Turow-Paul 2016].

Tellus and SEI

A second example is provided by the 'Great Transition' called for by the Tellus Institute to 'advance a planetary civilization rooted in justice, well-being, and sustainability' [Tellus]. Its founding president [Paul Raskin] is a member of the Club of Rome [Club of Rome] and an ecotopian futurist [Raskin 2016]. He is also in charge of the US centre of the Stockholm Environment Institute [SEI]. The latter was named after Strong's UN 1972 Stockholm Conference and joined the Boston-based Tellus Institute in setting up the Global Scenario Group (GSG) in 1995, arguing for a 'Great Transition' to a 'planetary phase of civilization'. Together with Stockholm University and the Beijer Institute, SEI is at the basis of the Stockholm Resilience Centre. One of Tellus' fellows [Gus Speth] is the founder of the World Resources Institute (WRI), now controlled by the WEF network and a close ally of EAT. Tellus/SEI's GSG fed the Global Environment Outlook series from UNEP. Its work has been continued by Tellus' Great Transition Initiative (GTI), of which the website often reads as an esoteric Gaian manifest [e.g., Rockefeller 2015; Macy 2018].

The Planetary Health Alliance

A 'Great Transition' of society to 'Planetary Health' has also been called for in the 'São Paulo Declaration on Planetary Health', published in the Lancet, supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and organized by the Planetary Health Alliance (PHA) [Myers et al. 2021, appendix]. The PHA was launched with support of the Rockefeller Foundation in 2016, is co-housed by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (home of Walter Willett), and wishes to 'achieve a Great Transition' [PHA]. The Lancet, THI (with Willett on the Board of Directors), the United Nations Foundation, Project Drawdown, WWF, the International Futures Forum, Plant-based Health Professionals UK, and SEI are members of the Alliance [PHA]. Some of the signatories of the São Paulo Declaration have an outspoken anti-livestock agenda, such as 50by40, Beyond Meat, and The Good Food Institute [see above]. Other signatories include WWF, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), and the True Health Initiative (THI, with Willett on its Board of Directors). The document itself is a New Age-ish pamphlet asking 'spiritual leaders of all faiths' to 'expand the mindset of humanity to embrace ancient teachings and wisdom' and 'to utilize religious and spiritually affiliated institutions for Planetary Health education'. Unsurprisingly, 'plant-based' diets are part of the intention [De La Torre 2021].

The strategy of EAT’s Great Food Transformation is top-down and interventionist, proposing hard policy measures to bypass the 'whim of consumer choice’. Such policy options make use of fiscal and economic incentives, as well as legal measures. These range from the mandatory use of nutritional warning labels, over the application of 'sin taxes', to the banning of meat from menus.

A call to overrule consumer choice

The EAT foundation is among the most aggressive proponents of dietary interventionism, aiming to achieve a worldwide 'Great Food Transformation'. For an overview of practical proposals and examples of such interventionism, see elsewhere. EAT's interventionist top-down philosophy is in contrast to what developmental studies generally argue for, being the crucial importance of bottom-up governance [Kaiser 2021]. History has shown that top-down policies that propagate utopian schemes and aim to be world-spanning typically come with a specific deep structure of human and natural resource control, dispossession, exploitation, and blatant self-legitimization [Scott 1999; Shoup 2015].

The whim of consumer choice

The EAT-Lancet Commission is in favour of hard interventionism. It stipulates that 'countries and authorities should not restrict themselves to narrow measures or soft interventions' because 'the scale of change to the food system is unlikely to be successful if left to the individual or the whim of consumer choice' (emphasis added) [Willett et al. 2019]. The call to consider hard policy levers (including the restriction of dietary choice) has been supported by other partners within the EAT network, such as the World Wildlife Fund [WWF 2020] and World Resources Institute [Ranganathan et al. 2016].

The FOLU Roadmaps

The Food and Land-Use Coalition (FOLU), launched in 2017 to transform the global food system by 2050 based on the EAT-Lancet guidelines, has stated that it will 'go deep into the policy, regulatory environment, and businesses of individual countries' (emphasis added), starting with Colombia, Indonesia and Ethiopia, and targeting the Nordics, Australia, and Europe next [EAT 2020]. For Colombia, the focus is reasonably on less ultra-processed foods and more regenerative farming rather than a shift to EAT-Lancet prescriptions [FOLU 2019a,b]. Australia, however, should aim at a 91-% decrease in red meat consumption by 2050, directing its production at export [FOLU 2019]. For China, in contrast, there is 'no policy that forces people to change their diet', so that an increase in pork, poultry, fish, and milk is foreseen for 2050 [FOLU 2019].

C40 Cities

On the first day of the Third EAT Forum in 2017, the C40 Food Systems Network was launched. In 2019, the C40 Cities initiative announced its 'Good Food Cities Declaration', signed by the Mayors of 14 global cities. These Mayors engaged themselves to steer their citizens towards the EAT-Lancet Diet by 2030 [C40 2019], setting both a progressive (16 and 90 kg/p/y of meat and dairy, respectively) and ambitious target (zero meat and dairy) [C40 2019]. Some C40 cities have already introduced attempts to meet those targets, especially by reducing the availability of meat in public canteens [WEF 2020; Ajuntament de Barcelona 2020; Aass Kristiansen 2022].

Interventionist toolbox

Options proposed by the EAT-Lancet Commission and its close allies, such as WRI, WWF, WEF, and the Wellcome Trust (LEAP), typically encompass the use of marketing campaigns and nudging towards plant-derived products [using 'supportive narratives'; WEF 2019]. This is done, for instance, by giving more appealing names to meat and dairy 'alternatives' [Gavrieli et al. 2022], developing digital behaviour change interventions [Stewart et al. 2022], interfering with supermarket display, stimulating 30-day diet challenges (of the 'Veganuary' type), and modifying dietary guidelines. Harder policy options make use of fiscal and economic incentives, as well as legal measures ranging from the mandatory use of nutritional warning labels, over the application of 'sin taxes', to the banning of meat from menus [de Boer et al. 2014; Ranganathan et al. 2016; Springmann et al. 2018; WWF 2020; Minelli et al. 2021].

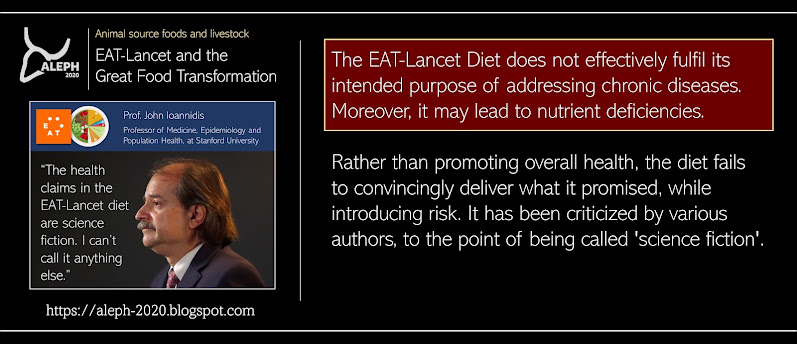

Commentary on EAT-Lancet's health assumptions is addressed elsewhere on this website, but has also been formalized in literature [Adesogan et al. 2020; Leroy & Cofnas 2020; Zagmutt et al. 2019a, 2019b, 2020; Vieux et al. 2022; Stanton 2024]. The diet has been dismissed as 'science fiction' by prof. John Ioannidis [quoted in Bloch 2019], who is 'one of the most-cited scientists of all times in the scientific literature [and] recognized as the leading clinical research methodologist of his generation for his work in evidence-based medicine and in appraising and improving the credibility of scientific studies and results' [Stanford Medicine].

While some observational studies do suggest potential protective effects [Stubbendorff et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2022; Colizzi et al. 2023; Ojo et al. 2023; Ye et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2023], others do not or give mixed results. In the NutriNet-Santé cohort, no significant association between the diet and the risk of cancer and cardiovascular was seen [Berthy et al. 2022]. In the EPIC-Potsdam cohort, higher adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet did not lead to a significant decrease in inflammatory biomarkers on the long run [Koelman et al. 2023]. In the EPIC-Oxford cohort, beneficial associations for ischaemic heart disease and diabetes were found, but not for stroke and all-cause mortality [Knuppel et al. 2019]. In the UK Biobank cohort, very small negative associations with cancer (only for males, and not for colorectal or prostate cancer) and all-cause mortality were found, but not with cardiovascular disease [Karavasiloglou et al. 2023].

An additional problem is that such observational studies are prone to residual confounding, especially by healthy user bias in Western countries [see elsewhere]. Both of the two UK-based studies cited above (EPIC-Oxford and UK Biobank) reported that those with the highest EAT-Lancet scores were more likely to follow healthier lifestyles, introducing likeliness of residual confounding [Stanton 2024]. Given the planetary ambitions of the EAT-Lancet diet, it is important to point out that when tested across continents and cultural settings, the diet does not deliver what it promises with respect to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes [PURE cohort; Mente et al. 2023].

Adding to the heterogeneity in results, there are also indications that individuals may respond differently depending on genetic variations [Zhang et al., 2023]. More worryingly, however, the EAT-Lancet diet also comes with risks due to nutrient security, as it is deficient in several key micronutrients [Young 2022; Beal et al. 2023; Nicol 2023].

Further reading (summary of the literature):

Criticism: general

Although the diet is promoted as universally favourable for human health and the planet, it received mixed feedback consisting of appraisal and criticism [Tulloch et al. 2023]. The diet has generally been criticized for being alarmist, lacking scientific rigor, and holding uncertain assumptions [Kaiser 2021], and for its lack of methodological transparency [Thorkildsen & Reksnes 2020].

The problem with public-private partnerships

Within the Davos public-private partnership system, the private partners obviously expect substantial benefits from their public counterparts (loosening of regulations, bailouts when crisis develops, expansion of domestic investment markets through commodification, financialization, and privatization of public assets, government contracts and subsidies, etc.) [Shoup 2015]. They operate without borders as well as above and beyond national regulatory structures. Civil society, on the other hand, is not able to evolve as fast in adapting to the challenges of the global era and cannot, therefore, effectively resist a corporate takeover of its governments [Scott 1999; Rothkopf 2009]. This is especially true when resistance to neoliberal policies diminishes due to societal shock (e.g., an economic crisis or pandemic) [Shoup 2015].The public-private partnership concept was introduced in 1997 by Maurice Strong in a reform proposal as 'consultation between the UN and the business community' [Rosett & Russell 2007]. Such partnerships have been criticized for their lack of democratic responsibility and for overvaluing the status of unaccountable private actors and foundations in shaping the global development agenda and providing public goods and services [Global Policy Watch 2019]. The model constitutes an undemocratic conscription of 'corporate money and power to force through a social and political agenda - without the bother of going through the ballot box' [Stuttaford 2020a,b]. It has been pointed out that some of the transnational corporations involved in such partnerships are among the 'worst examples of Northern development strategy' and 'biggest contributors to cultural and environmental destruction in the South' [Chatterjee & Finger 1994].

Sociocultural issues

Criticisms refer to EAT's underestimation or even neglect of the broader ecological, cultural, and socio-economic context [Gebreyohannes 2019; Gupta & Bharati 2019; Torjesen 2019; Tuomisto 2019; Adesogan et al. 2020; Burnett et al. 2020; Katz-Rosene 2020]. Socially, its budgetary impact may be too high for the world's poor [Hirvonen et al. 2019; FAO 2020], whereas upper middle-class bias is visible in the frequent use of 'plant-based' influencers and chefs [EAT 2019]. The Planetary Health Shopping List further illustrates this, by referring to such items as tahini, olive oil, avocados, and sushi sheets [EAT 2019]. The suggestive depiction of India and Indonesia as near-vegetarian models to stay 'within the planetary climate boundary for food' [Loken & DeClerck 2020], is little more than a romanticized Western viewpoint [see elsewhere]. As such, the EAT-Lancet diet contradicts actual dietary preferences in these regions [Karpagam et al. 2020] and passes lightly over the undernourishment of parts of their populations [cf. high stunting rates of 30-40% in Indian and Indonesian children; Adesogan et al. 2020].

Environmental issues

Adding to critique on its societal relevance, the diet's premises have been questioned for being unrealistic, potentially creating harmful environmental trade-offs. For instance, the vast increase in nut production would lead to water stress [Braich 2019; Vanham 2020]. Gains in sustainability by lowering greenhouse gas emissions may come with the trade-off of a higher total water footprint [Ye et al. 2023]. The diet insufficiently takes into account circularity aspects in the food system [van Selm et al. 2022].